Stories. Writings. Insights.

Stories. Writings. Insights.

Stories. Writings. Insights. Stories. Writings. Insights.

Witnessing the world and rewriting its memory.

Protecting the River That Flows Through D.C.’s Veins

The work keeping the historic Potomac River safe.

Photo of the Potomac River (Credit: Virginia Tourism)

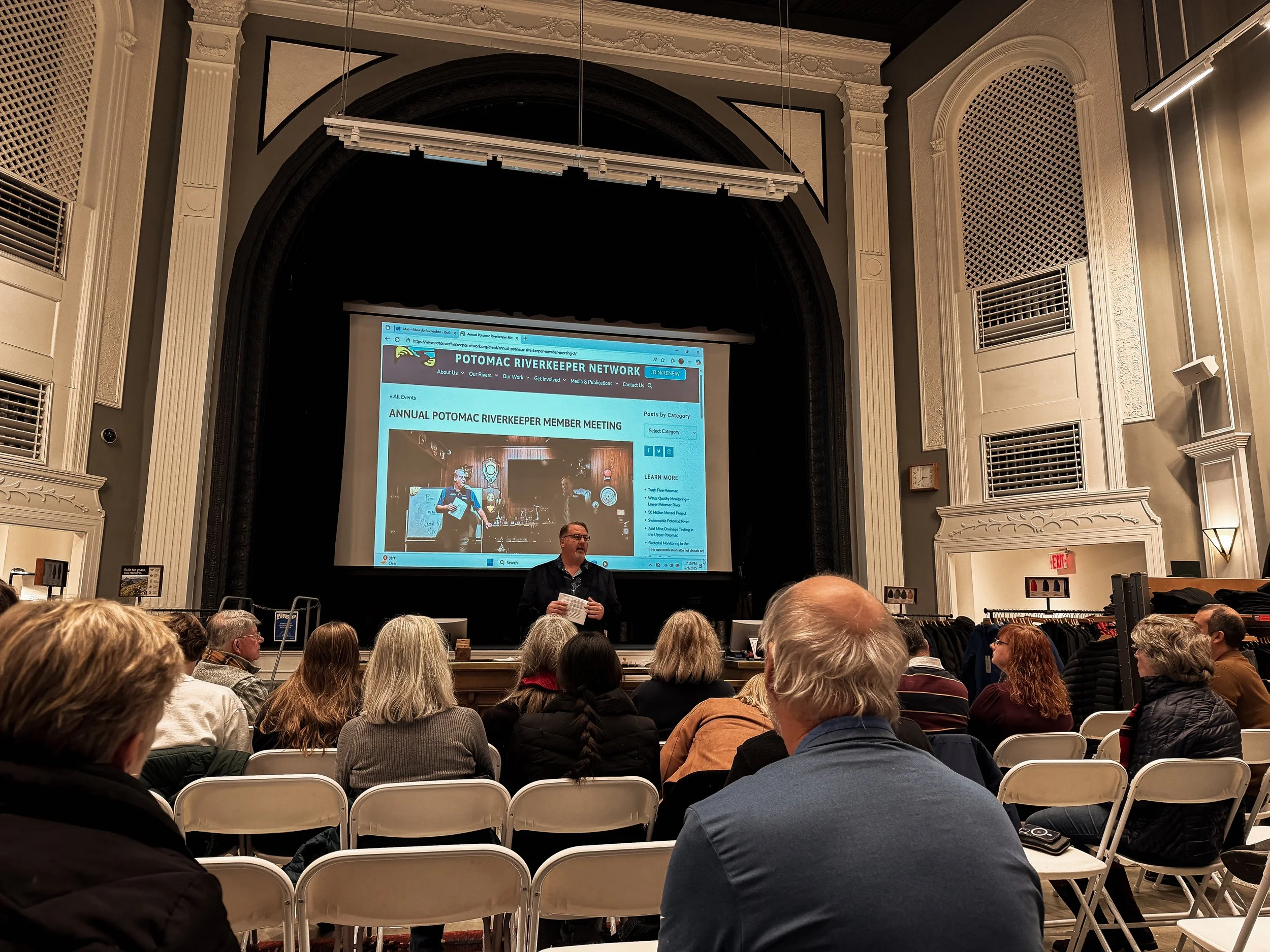

WASHINGTON—For decades, polluted runoff, toxic chemicals and aging sewage systems have left the Potomac River with invisible public-health risks. Now, with weekly sampling and legal intervention from the Potomac Riverkeeper Network (PRKN), the waterway is shifting towards cleaner, safer conditions, marking measurable progress in a river once labeled a “national disgrace” by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1965.

“Our mission is simple,” said Potomac Riverkeeper Dean Naujoks. “We stop pollution to protect the public’s right to clean water.”

Naujoks and a team of staff scientists, community volunteers, and pro bono attorneys are attempting to close a long-standing oversight gap: the disconnect between environmental law and actual enforcement on the water. Their work includes weekly sampling at recreation sites, drone investigations, permit reviews and lawsuits, functioning as a real-time check on whether agencies, industries and municipalities comply with water-quality laws. When agencies delay action, PRKN sues, providing a model of community-driven environmental accountability.

This approach arrives at a moment when contamination sources are shifting away from visible discharges toward emerging threats like per- and polyfluoroalkyl substanances (PFAS), chemicals linked to cancer and bioaccumulation in fish consumed in communities that rely on subsistence fishing.

The Problem

According to Naujoks, PFAS levels in fish at Piscataway Creek downstream of Joint Base Andrews “have exceeded EPA drinking water standards by more than 140 million times” in some samples, exposing families who fish for regular meals.

“These chemicals aren’t just in the water,” he said. “They’re in people’s bodies. They’re in their children. It’s generational exposure.”

At the same time, untreated sewage is still periodically discharged into the river during storm events. Washington, D.C., is constructing multi-billion-dollar tunnel systems to contain that overflow, but final completion is not projected until 2030.

“We’ve fixed major pollution sources,” Naujoks said, “but not all of them. The Potomac will be measurably cleaner in 2031 than it is today.”

Dean Naujoks speaks more about PRKN’s mission. (Video by Misha Bernard-Lucien)

PRKN’s Solution

PRKN runs its widely used Water Quality Monitoring Program, where volunteers collect weekly samples at recreation zones along the Potomac and its tributaries.

“When I first got here, nobody was monitoring,” Naujoks said, referring to agency-level sampling before 2019. “D.C. was testing in the middle of the channel once a month. That didn’t tell the public anything.”

Now, results are posted online every Thursday, creating an immediate, public-facing record of which areas are swimmable and which are not. That transparency forces accountability by name.

The enforcement branch follows an evidence-first model: sampling leads to letters of violation, and if agencies fail to intervene, PRKN files suit under the Clean Water Act.

That litigation has pushed Alexandria into a $615 million sewer upgrade, compelled the Navy to apply for a pollution permit for weapons-testing discharge, and forced multiple treatment facilities into compliance orders.

“You can argue science in public, but you cannot misrepresent facts in court,” Naujoks said.

Background on the Potomac: A Riverline Dividing Freedom and Slavery

The Potomac has always been more than a water system: it has served as a symbolic boundary in America’s racial history.

Across the Civil War era, the Potomac functioned as both a dividing line between free and slave states and a crossing into imagined freedom. Maryland remained a slave state until 1864; enslaved Black people often crossed tributaries near what is now the Wilson Bridge, fleeing toward Washington, where the Union Army fortified the riverfront.

Sites now known for biking, running and waterfront dining once formed part of the “River Road corridor,” where Black families settled following emancipation, many working as farmers, watermen, boat haulers, and domestic laborers.

PRKN’s Progress

Standing on the riverbank, Naujoks says he gets his urgency from witnessing change firsthand.

“When I started, sewage was overflowing into this river every time it rained,” he said. “Now we’re tracking it in real time, forcing investment, and protecting people who rely on this water. That’s the legacy.”

He continues.

“If we don’t speak for the river, who will?”

DC Water’s Race Against Time: The Push to Eliminate Lead Pipes by 2037

Construction workers replace lead pipe in Northwest D.C. (Photo by Misha Bernard-Lucien)

WASHINGTON—Washington, D.C. is in a race against time and trust. Beneath the District’s historic buildings and roads, thousands of aging lead pipes carry drinking water into homes. For the DC Water and Sewer Authority, removing every one of those pipes by 2037 is not only a logistical challenge but a public health imperative.

At the forefront of that effort is William Elledge, director of Capital Water Programs and the Lead-Free DC initiative. With more than 25 years of experience in planning and pipeline construction, Elledge has spent the past decade shaping DC Water’s infrastructure projects and now, its ambitious public health mission.

“The health impacts are primarily neurological,” Elledge said in an interview. “They can lead to developmental delays, learning disabilities and attention problems, especially in children under seven. We’re particularly interested in achieving a health benefit for little kids and women who are nursing or pregnant.”

William Elledge

Director of Engineering and Technical Services at DC Water. (Photo courtesy of DC Water)

While DC Water ensures that treated water leaving its facilities is lead-free, contamination can occur when that water passes through aging service lines made of lead, relics from a time when the material was prized for its durability and pliability.

“From a construction perspective, lead was actually a very functional material,” Elledge said. “It’s strong, it’s easy to work with and repair, and it lasts a long time. We just didn’t know about the health impacts back then.”

The Lead-Free DC initiative, launched in 2019, aims to replace roughly 42,000 lead service lines citywide. When the program began, DC Water estimated the total at 28,000, but further investigation revealed a higher number. Elledge said the agency is still on track to meet its original goal for the first 28,000 replacements by 2030 and anticipates finishing the remainder by 2037: the federal deadline set by the Environmental Protection Agency’s Lead and Copper Rule Improvements (LCRI).

Funding, however, remains one of the program’s biggest hurdles. The D.C. Council allocated $8.5 million in fiscal year 2022 to help cover the full cost of lead pipe replacements on private property when DC Water replaces the public portion. But with tens of thousands of pipes still in place, the price tag continues to grow.

“The biggest thing is money,” Elledge said. “We need more federal funding and district support where possible. The Council continues to appropriate a small amount of money each year, but it only funds one particular program for a couple of months. After that, we rely on DC Water’s funds and federal assistance.”

Even with funding, the agency faces another unexpected challenge: convincing residents to participate.

“This is a program that has no direct cost to the homeowner,” Elledge said. “It has a health benefit and increases property value, yet we still have to convince people to let us do it.”

DC Water’s team of “activators,” trained residents hired through a partnership with the Department of Employment Services (DOES), goes door to door explaining the program and seeking homeowners’ consent. The approach doubles as a workforce development initiative, offering job training and stable employment to D.C. residents.

“It’s just a fantastic side benefit,” Elledge said. “We’re not only addressing health impacts and doing construction work, but we’re also helping people find solid employment.”

Even so, participation hovers around 80 to 90 percent per block. Some residents refuse to sign the access form, often citing privacy concerns or skepticism. Without a citywide mandate, DC Water cannot compel replacements.

Another challenge DC Water faces is maintaining trust. Given the country’s history, the 2014 water crisis in Flint, Michigan, left deep scars on public confidence in government-led water safety initiatives. In a post-Flint era, skepticism is a factor to consider.

“To build trust, we make sure we’re transparent,” Elledge said. “If you live in the district, you can go to dcwater.com/lead, type in your address, and see what kind of service line you have. We even show how confident we are in that data: verified, suspected, or unknown.”

The agency’s Lead Service Line Inventory Map allows residents to see their neighborhood’s risk level and encourages transparency about infrastructure conditions. That openness, Elledge believes, is key to restoring faith in public utilities.

Community response has been somewhat positive, he added. Though most utility hotlines received complaints, DC Water’s lead hotline occasionally receives “thank-you” calls from residents who appreciated the crew’s communication, flexibility, or consideration during stressful times.

Still, common complaints persist. “Our number one complaint is restoring the front yard,” Elledge said. “We dig a hole or two, and people naturally want their lawns to look like they did before. We do our best to make sure that happens.”

DC Water’s collaborations extend beyond DOES. The Department of Energy and Environment (DOEE) partners with the utility to handle past “partial replacements,” where only one side—public or private—was replaced. The Department of Health provides residents with additional resources about lead exposure and testing.

Despite the governmental hurdles, Elledge remains optimistic. “When you have a higher purpose, you’re going to push through,” he said. “We know that what we’re doing has a generational impact. Water is life.”

As for the residents of D.C., Elledge has one main request: check your address and sign up. “Even if we’re not coming to your neighborhood for another eight or nine years, we still need people to sign up,” he said.

About DC Water

The District of Columbia Water and Sewer Authority (DC Water) was established in 1996 as an independent authority to provide drinking water, wastewater collection, and treatment services to D.C. residents. The agency operates more than 1,300 miles of water mains, 1,800 miles of sewer lines, and the Blue Plains Advanced Wastewater Treatment Plant, one of the largest in the world.

Photograph of DC Water (Photo by Misha Bernard-Lucien)

Under the oversight of the D.C. Council’s Committee on Transportation and the Environment, DC Water manages billions in infrastructure assets and oversees projects like Lead-Free DC that aim to modernize the city’s aging water system while safeguarding public health.

As Elledge put it: “[DC Water is] not just replacing pipes, we’re protecting future generations.”

Considering a Clean D.C.

With lead service lines posing major health risks to the residents in Washington, D.C.,Bill 26-92 Lead-Free DC Omnibus Amendment Act of 2025 was introduced on Jan. 29 to ensure that all lead service lines in D.C. are replaced with non-lead lines by Dec. 31, 2030.

Photograph of DC Water (Photo by Misha Bernard-Lucien)

WASHINGTON—With lead service lines posing major health risks to the residents in Washington, D.C., Bill 26-92 Lead-Free DC Omnibus Amendment Act of 2025 was introduced on Jan. 29 to ensure that all lead service lines in D.C. are replaced with non-lead lines by Dec. 31, 2030.

Efforts to provide clean water in the D.C., Maryland and Virginia area have been led by environmentally conscious groups such as DC Water and Dream.Org, with additional support from the Committee on Transportation and the Environment. Bill 26-92 was introduced by Councilmember Brooke Pinto and co-introduced by Councilmember Charles Allen, who also chairs the committee, along with several other councilmembers.

The Lead-Free DC Omnibus Amendment Act builds on earlier legislative efforts. It was first introduced in 2023 as a continuation of progress made through the progress through the Clean Energy Omnibus Amendment Act of 2018, which Mayor Muriel Bowser signed into law in 2019. That act marked a significant step forward in D.C.’s climate and environmental initiatives.

While steady progress has been made since then, replacing lead pipes across the city has been an ongoing challenge. Although the bill and DC Water operate separately, both aim to create a lead-free D.C., a process that has not always moved as smoothly as residents have hoped.

In 2024, residents participating in DC Water’s Lead-Free Initiative reported issues such as holes in walls, reduced water pressure, lawn damage and sink holes during pipe replacement work.

Efforts to interview Councilmembers Brooke Pinto and Charles Allen or their teams went unanswered, and attempts to speak with D.C. Water were unsuccessful.

Inside the Movement Bringing Environmental Advocacy to the DMV

WASHINGTON—This year in July, President Donald J. Trump signed an executive order inaugurating “a golden age” for a data center boom. These large-scale industrial facilities are raising concerns for green policy advocates like Dream.Org: Green For All.

Jasmine Davenport speaks about Green For All. (Video by Misha Bernard-Lucien)

WASHINGTON—This year in July, President Donald J. Trump signed an executive order inaugurating what his administration described as “a golden age” of accelerated data-center construction nationwide. The move positions the expansion as technological progress, but environmental advocates warn that the rapid growth of industrial-scale data centers could deepen environmental inequities in communities already historically burdened by pollution exposure.

Dream.Org’s Green For All program is among the groups responding. The organization focuses on environmental education, equity and access for populations often excluded from policy discussions surrounding economic development and clean-energy investment. Advocates say that as new infrastructure projects unfold, communities with long histories of environmental exposure will need tools to participate in permitting, zoning and environmental oversight processes.

“Black women are predestined to early labor in birth… low birth rates, and premature babies,” said Jasmine Davenport, senior director of Green For All. Among many reasons, one “is because we have been breathing in bad air for years.”

Jasmine Davenport

Senior Director for Dream.Org’s “Green For All”

Photo by Misha Bernard-Lucien

The Generational Impacts of Environmental Disparities

According to Green For All leadership, the environmental disparities facing Black communities are not new. Senior Director Jasmine Davenport said the roots are documented and trace back to federal housing segregation.

“This goes back to redlining,” Davenport said. “They did not want us [Black residents] in neighborhoods where we could breathe easily, so we were destined to be put into neighborhoods where there was bad environmental air quality.”

Davenport referenced federal New Deal-era housing maps that placed Black residents near industrial corridors, manufacturing facilities, transportation hubs and regions with lower air quality. Those zoning patterns resulted in generations of exposure linked to respiratory illness, high asthma rates, and maternal health disparities.

Research has repeatedly shown that Black women experience higher rates of preterm labor, low-birth-weight outcomes, and chronic respiratory complications. Davenport pointed to those statistics as evidence of the lingering effect of environmental policy.

Data-Center Development

Program assistant Naomi Garcia-Hector said that while historical evidence remains well-documented, a new environmental pressure point is emerging: data-center development.

“Data centers are proliferating across the country, and particularly are popping up in Black and brown communities where they are taking up resources, water, energy, and they put strain on the grid,” Garcia-Hector said.

Naomi Garcia-Hector

Dream.Org Program Assistant

Large-scale centers can consume power equivalent to thousands of households, place a strain on municipal grids and require substantial water usage for cooling systems. Advocates warn that the facilities are frequently proposed in locations with lower land costs, often aligning with communities historically affected by zoning and displacement.

Environmental groups say that new corporate development risks replicating past patterns unless residents are informed and able to participate in decision-making.

Educating Residents on Their Role in Policy

Garcia-Hector said Dream.Org is working to close the gap between development approvals and community awareness. Much of that work centers on teaching residents how to intervene before facilities break ground.

“We make sure to cut through the jargon so that people actually understand what is happening and how they can be advocates themselves,” she said.

Dream.Org has been hosting informational sessions, encouraging public testimony at local meetings and preparing residents to submit public comments during environmental review periods. The organization’s Power in the Problem campaign connects residents to tools, sample language and policy updates.

Davenport said that empowering community response is essential to shifting long-term outcomes, especially when dealing with infrastructure that has multigenerational impact.

Policy, Equity and Opportunity

Although accountability work remains ongoing, Davenport said part of the solution also involves expanding access to economic pathways within the environmental workforce. Green For All’s additional programming includes workforce placement strategies for justice-impacted individuals and support for HBCU students interested in green-sector careers.

She said solutions must extend beyond awareness and protest; they must also advance economic participation.

“We have to make sure that we are speaking up for what is going to benefit our communities and making sure that we have a voice in everything that is going on,” Davenport said.

Garcia-Hector emphasized that meaningful advocacy begins with information rooted in resident experience.

“People deserve information that helps them advocate for their own neighborhoods,” she said.