Protecting the River That Flows Through D.C.’s Veins

Photo of the Potomac River (Credit: Virginia Tourism)

WASHINGTON—For decades, polluted runoff, toxic chemicals and aging sewage systems have left the Potomac River with invisible public-health risks. Now, with weekly sampling and legal intervention from the Potomac Riverkeeper Network (PRKN), the waterway is shifting towards cleaner, safer conditions, marking measurable progress in a river once labeled a “national disgrace” by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1965.

“Our mission is simple,” said Potomac Riverkeeper Dean Naujoks. “We stop pollution to protect the public’s right to clean water.”

Naujoks and a team of staff scientists, community volunteers, and pro bono attorneys are attempting to close a long-standing oversight gap: the disconnect between environmental law and actual enforcement on the water. Their work includes weekly sampling at recreation sites, drone investigations, permit reviews and lawsuits, functioning as a real-time check on whether agencies, industries and municipalities comply with water-quality laws. When agencies delay action, PRKN sues, providing a model of community-driven environmental accountability.

This approach arrives at a moment when contamination sources are shifting away from visible discharges toward emerging threats like per- and polyfluoroalkyl substanances (PFAS), chemicals linked to cancer and bioaccumulation in fish consumed in communities that rely on subsistence fishing.

The Problem

According to Naujoks, PFAS levels in fish at Piscataway Creek downstream of Joint Base Andrews “have exceeded EPA drinking water standards by more than 140 million times” in some samples, exposing families who fish for regular meals.

“These chemicals aren’t just in the water,” he said. “They’re in people’s bodies. They’re in their children. It’s generational exposure.”

At the same time, untreated sewage is still periodically discharged into the river during storm events. Washington, D.C., is constructing multi-billion-dollar tunnel systems to contain that overflow, but final completion is not projected until 2030.

“We’ve fixed major pollution sources,” Naujoks said, “but not all of them. The Potomac will be measurably cleaner in 2031 than it is today.”

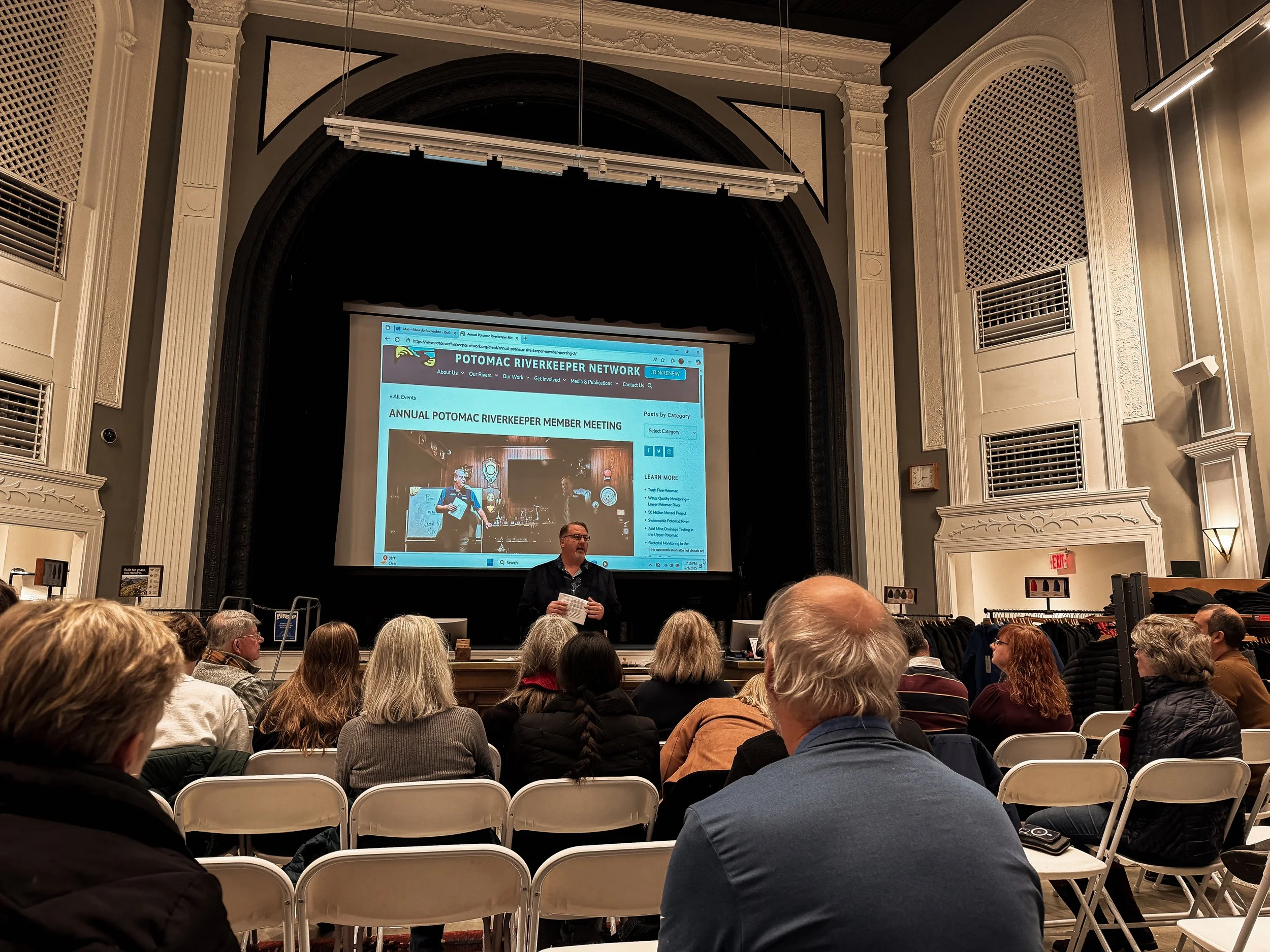

Dean Naujoks speaks more about PRKN’s mission. (Video by Misha Bernard-Lucien)

PRKN’s Solution

PRKN runs its widely used Water Quality Monitoring Program, where volunteers collect weekly samples at recreation zones along the Potomac and its tributaries.

“When I first got here, nobody was monitoring,” Naujoks said, referring to agency-level sampling before 2019. “D.C. was testing in the middle of the channel once a month. That didn’t tell the public anything.”

Now, results are posted online every Thursday, creating an immediate, public-facing record of which areas are swimmable and which are not. That transparency forces accountability by name.

The enforcement branch follows an evidence-first model: sampling leads to letters of violation, and if agencies fail to intervene, PRKN files suit under the Clean Water Act.

That litigation has pushed Alexandria into a $615 million sewer upgrade, compelled the Navy to apply for a pollution permit for weapons-testing discharge, and forced multiple treatment facilities into compliance orders.

“You can argue science in public, but you cannot misrepresent facts in court,” Naujoks said.

Background on the Potomac: A Riverline Dividing Freedom and Slavery

The Potomac has always been more than a water system: it has served as a symbolic boundary in America’s racial history.

Across the Civil War era, the Potomac functioned as both a dividing line between free and slave states and a crossing into imagined freedom. Maryland remained a slave state until 1864; enslaved Black people often crossed tributaries near what is now the Wilson Bridge, fleeing toward Washington, where the Union Army fortified the riverfront.

Sites now known for biking, running and waterfront dining once formed part of the “River Road corridor,” where Black families settled following emancipation, many working as farmers, watermen, boat haulers, and domestic laborers.

PRKN’s Progress

Standing on the riverbank, Naujoks says he gets his urgency from witnessing change firsthand.

“When I started, sewage was overflowing into this river every time it rained,” he said. “Now we’re tracking it in real time, forcing investment, and protecting people who rely on this water. That’s the legacy.”

He continues.

“If we don’t speak for the river, who will?”